No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

God’s Nature and Relation to Creatures aims primarily at helping readers understand that the nature and attributes of the God of classical theism are both intelligible and coherent.

Paperback: $14.95 | Kindle: $9.99

“Well-trained in Thomistic epistemology and metaphysics, Bonnette is able to apply calm and rational responses to those who raise questions about the existence of God, the freedom of the will, the essential difference between humans and animals, and the possibility of miracles.” – Dr. Robert Fastiggi, Professor of Dogmatic Theology, Sacred Heart Major Seminary, Detroit, MI

“Dr. Dennis Bonnette’s work has had a very large impact — everything he writes gets noticed — no doubt due to his unwavering commitment to orthodoxy. Rational Responses to Skepticism is a true contribution to Catholic thought.” – Matthew Levering, James N. Jr. and Mary D. Perry Chair of Theology, Mundelein Seminary

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Atheistic Materialism’s Unseen Errors, written in purely rational terms of how reality actually is constituted in ways that materialism fails to grasp, shows many of the fundamental errors found in the widespread worldview known as scientific or atheistic materialism, a philosophical perspective that claims that nothing but physical things exist.

Paperback: $14.95| Kindle: $9.99

“Well-trained in Thomistic epistemology and metaphysics, Bonnette is able to apply calm and rational responses to those who raise questions about the existence of God, the freedom of the will, the essential difference between humans and animals, and the possibility of miracles.” – Dr. Robert Fastiggi, Professor of Dogmatic Theology, Sacred Heart Major Seminary, Detroit, MI

“Dr. Dennis Bonnette’s work has had a very large impact — everything he writes gets noticed — no doubt due to his unwavering commitment to orthodoxy. Rational Responses to Skepticism is a true contribution to Catholic thought.” – Matthew Levering, James N. Jr. and Mary D. Perry Chair of Theology, Mundelein Seminary

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Students of political science properly hunger for comprehensive approaches to political theory which place in theoretical perspective the major ideas which govern the world today. This book, originally published in 1978 by The Society for the Study of Traditional Culture, was written in response to what is in effect an intellectual vacuum. It attempts to provide the essential background necessary for an intelligent view of contemporary intellectual culture for the purpose of supplementing the undergraduate student’s readings in the works of primary authors and providing graduate students with a primer dealing with beginnings or elements of political theory.

Paperback: $19.95 | Kindle: $9.99

TBA

Richard J. Bishirjian was Founding President and Professor of Government at Yorktown University from 2000-2016. He earned a B.A. from the University of Pittsburgh and a Ph.D. in Government and International Studies from the University of Notre Dame.

Richard J. Bishirjian was Founding President and Professor of Government at Yorktown University from 2000-2016. He earned a B.A. from the University of Pittsburgh and a Ph.D. in Government and International Studies from the University of Notre Dame.

Dr. Bishirjian was Gerhart Niemeyer’s teaching assistant at Notre Dame. He was an assistant professor in the Department of Politics at the University of Dallas in Texas, chairman of the Political Science Department at the College of New Rochelle in New York and founder of Yorktown University where he served as President and Professor of government from 2000-2016.

He served as a political appointee in the Reagan Administration and in the Administration of George H. W. Bush.

He is the editor of A Public Philosophy Reader and author of three books, The Development of Political Theory, The Conservative Rebellion and The Coming Death and Future Resurrection of American Higher Education. His most recent work, “Coda,” is a novel published by En Route Books. His most recent three scholarly studies are Ennobling Encounters, Rise and Fall of the American Empire, and Conscience and Power.

Dr. Bishirjian’s essays have been published in Forbes, The Political Science Reviewer, Modern Age, Review of Politics, Chronicles, the American Spectator and The Imaginative Conservative.

For the full story, see Dick’s website.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

This book is as stated on its cover an assessment of a book by Charles Taylor entitled “A Secular Age” published in 2007. It serves mainly as a critique of Taylor’s book, which generally was received favorably, not only in religious academic circles, Taylor being Catholic, but also in the “secular” academic world engaged in the subject matter he was concerned with.

As may be appreciated, this latter part of the modern world of education, especially at the highest levels, would be commonly described as “secular” in an anti-religious, meaning atheistic, sense. The favorable reception of Taylor’s thesis in both seemingly opposed educational worlds is somewhat curious, prompting one to look more closely into its thesis and conclusions.

Dr. Boland is mainly concerned with challenging the book’s assertions from the point of view of a follower of the philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas. But, since its subject matter is most properly within the scope of social and moral philosophy, he is also concerned to show up its deficiency even from the point of view of the philosopher Aristotle.

The author’s assessment should therefore prove to be one of interest to both secular and religious readers, Catholic or not.

Paperback: $14.95 | Kindle: $9.99

I found Dr. Boland’s assessment of “A Secular Age” to be very informative. He first catches Taylor out using the word “secular” in an equivocal manner; assigning to it four significations, including one of his own invention. It is anyone’s guess as to which meaning the title of the book is meant to convey. Dr. Boland points out the specific meaning of the word as used in the Church. Taylor, a Catholic academic of high standing, seems oblivious to the simple and common sense meaning of the word “secular”, so frequently used in Church Teaching documents.

Taylor, as Dr. Boland emphasises, seems not to have grasped the first principle of Sociology: it is a practical science and not a theoretical one like mathematics. Taylor falls in with the modern and common academic misconception of Sociology and its resulting methodology. He fails to stand out from the crowd. What a pity. With guidance from St Thomas and Aristotle he would see why at bottom sociology is a practical science: because first and foremost it is an ethical science. Without this necessary insight and the assessment and commentary on Social questions that could and should go with it, an 800 page book on which ever of the four meanings Taylor associates in a particular “Age” with “Secular” can only be an attempt to fill a void with side issues and irrelevancies.

Popes St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI have been particularly strong in their addresses to Modern Secular Society (see e.g. their Addresses to the United Nations), on the need for the natural moral law to be a guiding legislative principle for all Nations and Societies. (For confirmation see my Assertions and Refutations “An Assessment of Dr. Tracey Rowland’s ‘Natural Law: From Neo-Thomism to Nuptial Mysticism’.”)

Another feature, or should I say debility, of “A Secular Age” Dr. Boland points up is Taylor’s lexical inventiveness. He uses words such as “porous” and “buffer”: words that seem to me to have been borrowed from the construction or building industry (Dr. Rowland is another Catholic trail blazer in this respect); words that one would expect to find on blue-prints for the Hoover Dam.

Dr. Boland has shown remarkable stamina with Taylor’s bloated book and much patience in commenting upon it. I highly recommend his assessment for the true Thomistic perspective it shines on “A Secular Age” (which ever of Taylor’s meanings you want to choose for “Secular” – he fiddles with “Age” as well) and the clear refutations of Taylor’s thesis it offers.

–Frank Calneggia, author of Assertions and Refutations: An Assessment of Dr Tracey Rowland’s Natural Law: From Neo Thomism to Nuptial Mysticism and editor of Analysing the Errors and Exposing the Real Agenda of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J.: The Selected Works of Frits Albers, Vol. 1

Donald G Boland Ll. B. (Sydney), Ph. D. (Angelicum) is a founding member of the Centre for Catholic Studies Inc. in Sydney Australia and is one of its former Presidents. He practiced for a number of years as a lawyer having a degree in law from the University of Sydney. Over much the same time, having obtained a doctorate in philosophy from the University of St. Thomas in Rome, he has taught philosophy and law in both Catholic and secular educational institutions, such as the University of Technology, Sydney, the University of Newcastle, the Aquinas Academy, the Centre for Thomistic Studies Inc., now operating under the name of the Centre for Catholic Studies Inc., and various Catholic seminaries, such as those of the Marists and the Vincentians. His doctoral thesis was on the concepts of utility and value in economics as found in the works of Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Selected for publication in this present volume are four of the principal works of Frits Albers wherein the errors of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., are exposed and analysed in depth, their impact on critical areas of Catholic life made manifest, and Teilhard’s real agenda proved from Teilhard’s own words. These are:

The author shows that Teilhard’s agenda to spread his errors in the Church was continued after his death so that after Vatican II Catholics would be taught these errors were the ‘authentic interpretations’ of the Council. He further shows that this has had a most disastrous effect on Catholic life on a global scale. The author discusses and analyses in some depth and with much acumen the insidious preparation of this Teilhardian agenda and its widespread post conciliar implementation. He then turns his attention to the documents of Vatican II and shows that they can only be rightly understood (that is to say, in the light of Catholic Faith and right reason) when seen and accepted as a continuation of the uninterrupted Tradition (handing on of Revelation) that has always existed in the Church, and from which evolution has always been absent.

Paperback: $19.95 | Kindle: $9.99

I am old enough to remember the furore caused among the Catholic young and not so young with whom I had communication in the time after my attendance at the Law School of the University of Sydney, and during my attendance at the Aquinas Academy, on the publication, after his death, of the works of Teilhard de Chardin, prohibited to be published by the Church during his lifetime. The furore as I recall came to a head in the middle 1960s as the Second Vatican Council was ending or shortly afterwards. Dr. Woodbury was amongst the loudest in his condemnation of the materialist/scientistic evolutionism to be found in the works.

Apart from the moral consequences of its teaching, the inanity, even insanity, of the “theological science” propounded, as well as the equivocations and general sophistry in its popular propagation, were so obvious to us at the time that we hardly gave it another thought. We did not pay that much attention to the sensationalist “press” that these works evoked.

Being more interested in the revival of genuine Catholic thought in the likes of Chesterton and the books being written by a multitude of other marvelous English converts, such as Father Ronald Knox and Arnold Lunn, a mountaineer who invented the slalom ski event in the Olympics, we treated the “phenomenon” of de Chardin SJ as just another of the passing fashions to which the Catholic world had always been subject, and focused on the works of the Church’s “Common Doctor”, with their resources to retain the sanity of mind needed in our times, as at all times.

Little did we realise that many in the Church, especially amongst de Chardin’s confreres, the Jesuits, were giving a lot of thought to his “revelations”, seeing it as a vehicle to bring the Church up to date, as it was supposed was the intent of the Vatican Council.

For a time, we did not appreciate that the ideas of de Chardin were but a break out of a deeper disease/malaise in modern Catholic thought that had already been identified and condemned as strongly as possible by the Magisterium, namely, that “mother of all heresies”, Modernism.

It is only in more recent times, as the depth of this intellectual and moral darkness has become more “visible”, that I have come to realise that, far from being a passing “phenomenon”, de Chardin’s “scientific evolutionism” has grown, like a cancer, to such monstrous proportions that it seems to be ineradicable. For it is evident now that the “forces” of the Evil One (Malignus), or the smoke of Satan as Pope Saint Paul VI put it, have indeed entered the very inner halls of the governing “Curia” (Latin for caring part) of the Church.

If I had been aware of the work of Frits Adlers, who was well aware of what was happening even in the 1970s, and was describing it in detail in the books only now being published widely, I would have been much the wiser myself about the dire state of affairs the faithful was caught up in, like in a spider’s web.

However, better late than never, and no doubt in God’s providence, we now have the malign situation exposed in the most thoroughgoing way. It is up to us to have the courage to face it, and condemn the error and evil it represents.

I will add if I might my own view of de Chardin’s work, whose connection with Modernism can be traced quite clearly in retrospect. Like many of his generation, including Maritain, he was well educated in modern science, and greatly impressed with its power. But being deeply spiritual because of his Christian upbringing, he was also troubled by the apparent conflict between what he held by Faith and what his modern science told him was pure reason.

He looked for a way out of this dilemma and through intellectual contact with Bergson’s philosophy, expressed especially in his book “Creative Evolution”, believed he had found it. He befriended Bergson’s closest associate Edouard Le Roy and discussed things over a long period.

It is significant that Maritain was initially drawn to Bergson’s solution of his own dilemma – it became the prevailing solution of the day to the perceived view that human knowledge in science was mechanistic – but later through contact with the works of St. Thomas Aquinas (by the graces of his wonderful wife Raissa) Maritain was able to see through Bergson’s “evolution” philosophical solution.

Importantly, the Church authorities of the time were alert to this mistaken approach, apparently perceiving the pantheistic implications of Bergson’s thought, and banned his books.

De Chardin, one speculates, felt that this was either a misunderstanding of Bergson’s philosophy or, like many others both inside and outside the Church, an arbitrary exercise of ecclesiastical authority against the scientific search for truth.

In fact, as we can now see, thanks in great measure to Frits Albers’ work, de Chardin’s adoption of scientific evolutionism, which evidently was influenced by the vitalism/intuitionism of Bergson, fell also into Modernism. Sadly for those deceived by it, de Chardin’s philosophy of science was just another philosophical error by which the heresy of Modernism, masquerading as Christian theology, was able to be perpetuated in modern Catholic thinking.

— Dr. Donald G. Boland, author of Rev. Fr. Austin M. Woodbury, SM, PhD, STD and the Aquinas Academy (1945 – 1975); also see his Compendium

Frits Albers Ph. B (1921-2000) was born in Holland and studied under the Jesuits at Nijmegen during the 1940s. He emigrated to Australia in 1951, and travelled extensively within the south-east region of the ‘lucky country’. He joined the Department of Education in Victoria and worked as a high school teacher who specialised in mathematics, French and English.

In the early post Vatican II period he realised that the strange interpretations of the recently concluded Council that were being forced upon Catholics were under pinned by the same philosophy he had been taught in the 1940’s by the Jesuits at Nijmegen in the name of St Thomas Aquinas, but which in reality was the systematic Modernism of Pierre Teilhard De Chardin, S.J. Thus, in the early 1970’s he began writing articles and books to expose the philosophical root of these errors and aberrations of Teilhard De Chardin, and to defend Catholic Faith, clear thinking, and right philosophy.

The editor is a retired electrical engineer who worked for most of his professional career in the specialist area of power generation. In a sabbatical year, he completed post graduate research in the History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Melbourne. He has long loved the philosophy of St Thomas Aquinas.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

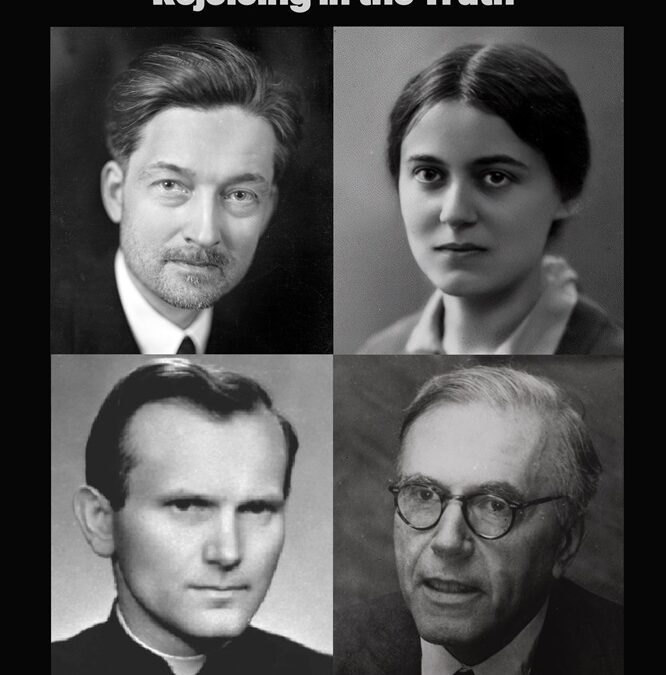

This book unfolds the intersecting life stories of four important Catholic philosophers of the 20th century, namely, Jacques Maritain, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrand, and Karol Wojtyla, and examines the salient themes of their respective philosophies. Exploring the lives of these four individuals will unlock for the reader the nature of Catholic philosophy, which always aspires to a higher wisdom and the discovery of the hidden harmony of the universe. The spiritual itinerary of these faithful scholars is part of a larger story, therefore, of the intimate relationship between faith and reason that is at the heart of Catholic intellectual life.

Paperback: $19.95 | Kindle: $9.99

“This book traces developments in Catholic philosophy during the 20th century by examining in some depth the lives and works for four important thinkers. Despite some philosophical differences, these four— Maritain, Edith Stein, von Hildebrand, and Pope John Paul II— shared important influences. All four clashed (in different ways) with Nazis; all four were heavily influenced (again differently) by the thought of St Thomas Aquinas, and of course all four practiced an intense Catholic faith. Spinello’s writing is lively and perceptive; his handling of philosophical themes will challenge readers without losing them.” – Philip E. Lawler, Director, Catholic Culture, Editor, Catholic World News

“This book is an absolute gem – and a must read – for anyone who loves Philosophy. Rejoicing in the Truth is the perfect subtitle for this truly outstanding book that so beautifully and accessibly presents the profound intellectual and moral wisdom of, arguably, the four greatest Catholic philosophers of the 20th century: Jacques Maritain, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrand, and Karol Wojtyla (best remembered and revered as Saint Pope John Paul II).” – Elizabeth B. Rex, MBA, PhD, ThD (cand.), former Adjunct Professor of Bioethics at Holy Apostles College & Seminary, and former Adjunct Professor of the Catholic Intellectual Tradition at Sacred Heart University.

“With Richard Spinello’s book we have the inspiring stories of four philosophers, Jacques Maritain, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrandt, and Karol Wojtyla, who confronted twentieth century ideologies of tyrannical evil and inhumane abuse with heroic courage and principled reason. Their development as Catholic philosophers is contextualized within the turbulent politics and cultures through which they lived, which poignantly reveals the enduring strength of the unity of faith and reason as the genuine perennial philosophy. This is a timely work. Readers can have their understanding and appreciation of the ongoing relevance of Catholic thought heightened so that the perennial philosophy can be welcomed as a source of fortitude and hope for challenging today’s daunting cultural and political deprivations.” – Thomas A. Michaud, author of After Justice: Catholic Challenges to Progressive Culture, Politics, Economics and Education

“Richard A. Spinello has written on the joyful pursuit of truth of four Catholics known for their contribution to philosophy, and also to theology: Jacques Maritain, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrand, and Karol Wojtyła. May a reflective reading of this work inspire others to courageously set on the adventurous path of truth, which ultimately leads us to Jesus Christ. I highly recommend this book.” – Very Rev. Peter S. Kucer, MSA, President-Rector, Holy Apostles College & Seminary, Cromwell, CT, and author of Catholic Church History: Pre-Christian to Modern Times

“In Four Catholic Philosophers, Professor Spinello has provided clear and insightful expositions of four of the most outstanding Catholic philosophers of the twentieth century — two of whom are canonized saints. For those wishing to understand authentic philosophy, illuminated by faith and reason, this book is highly recommended.” – Robert Fastiggi, Ph.D. Professor of Dogmatic Theology, Sacred Heart Major Seminary, Detroit, Michigan, and co-editor of with Jane Adolphe of Clerical Sexual Misconduct, Vol 2: A Foundational Conversation

“This engrossing read about four recent Catholic philosophers effectively combines biography with exposition of ideas: along the way it highlights how their shared realistic, personalistic, and metaphysically open vision, one grounded in sapiential faith, interior prayer, and spiritual perfection, is a helpful corrective to the idealistic, functionalistic, and positivistic or postmodern meanderings of contemporary thought.” – Dr. Alan Vincelette, Wilfred L. and Mary Jane Von der Ahe Chair of Philosophy, St. John’s Seminary, and author of Recent Catholic Philosophy: The Twentieth Century and A Reader in Recent Catholic Philosophy

“What a joy to read a profound and clear book about great Catholic philosophers of the 20th Century!” – Dr. Ronda Chervin, Catholic Professor and author of The Way of Love: The Path of Inner Transformation

“In the course of the twentieth century, Catholic theology obviously underwent tremendous changes – for better or worse is not perhaps clear yet. But what is not as obvious as the theological changes were the equally important philosophical developments that underlay them. This book serves as an introduction to four of the philosophers whose intellectual activity lay at the center of the historical trajectory of twentieth-century Catholic thought. To understand their work is a first step to understanding what are the real issues confronting the Catholic mind as we are close to completing the first quarter of the new century.” – Dr. Thomas Storck, editor of Money, Markets and Morals: Catholic Perspectives on Economics and Finance

“Four Catholic Philosophers: Rejoicing in the Truth invites us into the personal, academic, philosophical, and theological life experiences, and subsequent writings, of four Catholic philosophers who emerge from the political and ideological wreckage of the 20th century as perhaps the clearest voices of truth, intertwining faith and reason, in a world often devoid of both.” – Kiki Latimer, co-author with Dr. Stephen Schwarz of Philosophy Begins in Wonder

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.